Content

Celiac disease differs from IgE-mediated food allergies in several important respects. Celiac disease is NOT mediated by allergen-specific antibodies including IgE. Celiac disease is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction where symptoms develop 48-72 hours after ingestion of the offending food which is in contrast to IgE-mediated food allergies where symptoms develop rather quickly. But, celiac disease shares some common features with IgE-mediated food allergies also. Celiac disease is immunologically mediated, though not by antibodies. Celiac disease does affect only certain individuals in the population. And, most importantly, individuals with celiac disease must avoid the causative protein fraction, gluten, in their diets.

Celiac disease is also known as celiac sprue, non-tropical sprue, or gluten-sensitive enteropathy. This illness is a malabsorption syndrome occurring in sensitive individuals upon the consumption of wheat, rye, barley, and related grains (see Table 1). Celiac disease serves as the best example of delayed hypersensitivity reactions associated with foods.

Table 1: Cereal Sources of Gluten

|

Included on this page:

- Vocabulary

- Mechanism

- Symptoms and Sequelae

- Sources

- Causative Factor

- Prevalence and Persistence

- Management and Minimal Eliciting Dose

- Table: Gluten-Derived Ingredients

- Detection

- References

Celiac disease has gotten to be more complex with the discovery of non-celiac gluten sensitivity, an intolerance to gluten that does not have all of the diagnostic features of celiac disease.

In 2012, a multidisciplinary task force of physicians from seven countries met to review and evaluate the terminology for all of the conditions relating to gluten intolerance. They developed recommendations for the ideal vocabulary to describe these various conditions, the so-called Oslo definition for celiac disease and related terms. (see Vocabulary )

Vocabulary Evolution of Celiac Disease

- Coeliac / Celiac disease (CD)

A chronic small intestinal immune-mediated enteropathy precipitated by exposure to dietary gluten in genetically predisposed individuals.

Terms not currently recommended: SPRUE, COELIAC SPRUE, GLUTEN-SENSITIVE ENTEROPATHY AND GLUTEN INTOLERANCE, NON-TROPICAL SPRUE AND IDIOPATHIC STEATORRHOEA - Asymptomatic CD

Asymptomatic CD is not accompanied by symptoms commonly associated with CD and have no symptoms that respond to gluten withdrawal, even in response to direct questioning.

Terms not currently recommended: SILENT CD - Potential CD

Normal small intestinal mucosa in person at increased risk of developing CD as indicated by positive CD serology. - Subclinical CD

Unsuspected CD when the threshold of clinical detection without signs or symptoms sufficient to trigger CD testing in routine practice.

Terms not currently recommended: NON-CLASSICAL CD, LATENT CD - Symptomatic CD

Characterized by clinically evident gastrointestinal and/or extra intestinal symptoms attributable to gluten intake.

Terms not currently recommended: CLASSICAL CD, TYPICAL CD, ATYPICAL CD, OVERT CD - Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS)

Relates to one or more of a variety of immunological, morphological or symptomatic manifestations that are precipitated by the ingestion of gluten in people in whom CD has been excluded.

Term not currently recommended: GLUTEN SENSITIVITY - Gluten-related disorders

Recommended term to describe all conditions related to gluten. This may include disorders such as gluten ataxia, dermatitis herpetiformis, non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) and CD.

Term not currently recommended: GLUTEN INTOLERANCE

REFERENCE: Ludvigsson J. F., Leffler D. A., Bai J. C., et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut. 2013; 62: 43-52. https://gut.bmj.com/content/suppl/2012/02/15/gutjnl-2011-301346.DC1.html

Mechanism

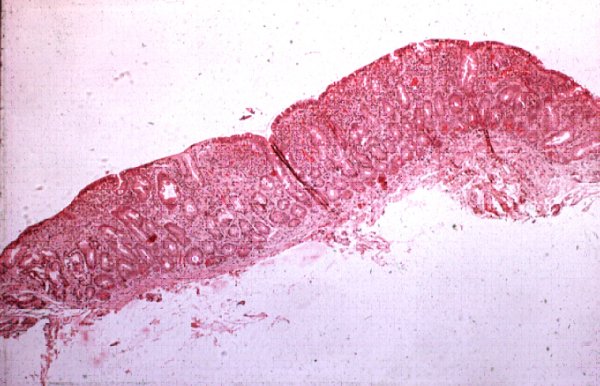

Celiac disease is an intestinal immune-mediated enteropathy precipitated by exposure to dietary gluten in genetically predisposed individuals. This enteropathy is a cell-mediated, localized inflammatory reaction occurring in the intestinal tract upon provocation with ingested gluten. The inflammatory reaction results in a so-called 'flat lesion' in the gut. The cell-mediated immunological reaction in the small intestine results in intestinal damage characterized by villous atrophy along with crypt hyperplasia, lymphoid infiltration of the epithelium, and edema of the lamina propria; the microscopic appearance of the small intestine is this 'flat lesion' (see Photographs 1 and 2). Once the damage appears, the absorptive function of the epithelium is impaired; increased fluid secretion into the intestinal lumen and enhanced permeability of the epithelium are also observed. Both digestion and absorption are impaired. The mucosal enzymes necessary for digestion and absorption are altered in the damaged cells. The absorptive cells are functionally compromised. The mucosal damage leads to nutrient malabsorption and affected individuals (if untreated) display features of nutrient deficiencies. It appears as though a defect in mucosal processing of gliadin (the prolamin protein found in wheat) in celiac patients provokes the generation of toxic peptides that contribute to the abnormal immunologic response and the subsequent inflammatory reaction.

Photograph 1: Photomicrograph of the normal small intestinal lining; note the villi that protrude into the intestinal lumen and absorb nutrients.

Photograph 2: Photomicrograph of the small intestinal lining from a patient with untreated celiac disease; note the absence of villi - the so-called 'flat lesion'

Symptoms and Sequelae

The symptoms of celiac disease are those associated with a severe malabsorption syndrome characterized by diarrhea, bloating, weight loss, anemia, bone pain, chronic fatigue, weakness, various nutritional deficiencies, muscle cramps, and, in children, failure to thrive. The risk of death is quite low, but untreated celiac disease is associated with considerable discomfort in many celiac sufferers. Also, individuals suffering from celiac disease for long periods are at increased risk for development of T cell lymphomas. Celiac patients also are more likely than others to have various other diseases especially diseases of an autoimmune nature including dermatitis herpetiformis, thyroid diseases, Addison's disease, pernicious anemia, autoimmune thrombocytopenia, sarcoidosis, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, IgA nephropathy, and Down's syndrome.

Because of the diminished absorptive function, celiac sufferers often have various nutritional deficiencies. In the most serious cases, insufficient calories are absorbed leading to failure to thrive in children and weight loss in adults. Other common nutritional deficiencies include iron deficiency manifested by anemia and calcium deficiency manifested by bone pain.

Celiac disease exists in a spectrum of severity among affected individuals. The most severely affected individuals suffer rather noteworthy symptoms until placed on an avoidance diet. But, many affected individuals have less severe symptoms making diagnosis much more challenging. For example, if anemia is the foremost symptoms, as it is in some celiac sufferers, there are numerous potential causative factors for anemia which often delays the diagnosis of celiac disease. Some, perhaps many, individuals suffer from latent (or silent) celiac disease. These individuals experience no noticeable adverse reactions upon ingestion of gluten but have anti-endomysial antibodies or other diagnostic features consistent with celiac disease. The likelihood that these individuals will later develop symptomatic celiac disease is unknown.

Table 2: Safety of Oats in Celiac Disease References

|

Sources

Celiac disease is associated with the ingestion of wheat, rye, barley, and related grains (see Table 1). While oats were once thought to be a causative factor in celiac disease, the role of oats has now been discounted by several relatively recent research studies (see Table 2). However, oats are often contaminated with wheat; this contamination occurs through shared agricultural fields, harvesting equipment, transportation vehicles, and on-farm and off-farm storage facilities. Thus, celiac sufferers should exercise caution with respect to the ingestion of oats. Gluten-free oats are now commercially available but their production takes great care to avoid contamination with wheat, rye or barley. Semolina (durum wheat), spelt, KAMUT®, einkorn, emmer, farro, and club wheat are basically varieties of wheat, and are also thought to trigger celiac disease in susceptible individuals. Triticale, a cross between wheat and rye, must also be avoided.

Causative Factor

The prolamin protein fractions of wheat, rye, and barley are the causative factors in celiac disease. Since the prolamin fraction of wheat is known as gluten, celiac disease is sometimes referred to as gluten-sensitive enteropathy. In wheat, the prolamin fraction is called gliadin, while it is called secalin in rye and hordein in barley. However, the prolamin proteins from these related grains are highly homologous and cross-reactive. Gliadin is the alcohol-soluble protein of the prolamin fraction and is the principal causative factor in the elicitation of celiac disease. However, the glutenin, or alcohol-insoluble fraction, is also likely involved. Since the prolamins are the major storage proteins in these grains, all varieties of wheat, rye, and barley are considered hazardous for celiac sufferers. The level of these proteins in wheat, rye, and barley is rather high.

The prevalence of celiac disease remains somewhat uncertain for several reasons. First, the diagnosis of celiac disease can on occasion be rather difficult. Celiac disease appears to be latent or sub-clinical in some individuals with symptoms only appearing occasionally. Furthermore, intestinal biopsies are needed to observe the 'flat lesion' in untreated individuals, an expensive and invasive procedure. Biopsies have been replaced by blood tests for certain antibodies that are associated with celiac disease (not causative but associated). These antibodies include the anti-endomysial antibody and the tissue transglutaminase antibody. The availability of these diagnostic tests has allowed the identification of individuals with latent celiac disease who do not have the 'flat lesion'. On this diagnostic basis, the prevalence of celiac disease in the U.S. is estimated at 1 in every 133 individuals (see Table 3). However, on the basis of diagnostic biopsies, the estimated prevalence is much lower at somewhere between 1 per 1000 or 1 per 2000 individuals.

The prevalence of celiac disease appears highest in certain European populations and in Australia, although this may relate to the frequency of usage of the more thorough diagnostic approaches. In the U.S., the prevalence of celiac disease is generally perceived to be much lower than in the EU. However, with the improved diagnostic testing, the estimated prevalence in the U.S. is higher and closer to that reported in the EU. However, many of these individuals would have latent celiac disease. Considerable variability is observed in the prevalence of celiac disease among various European populations but this may also be due to differences in diagnostic approaches.

Table 3: Prevalence of Celiac in USA Reference

|

Prevalence and Persistence

Celiac disease is a life-long condition. Although celiac disease may occur in a latent phase in some affected individuals, oral tolerance for gluten proteins does not seem to develop over time in affected individual (i.e. they are not known to outgrow this condition).

Management and Minimal Eliciting Dose

Celiac disease is treated by implementation of a gluten avoidance diet. Those with celiac disease attempt to avoid all sources of wheat, rye, barley, and related grains including a wide variety of common food ingredients derived from these grains (see Table 4). The need to avoid ingredients that do not contain protein from the implicated grains is somewhat debatable, but widely practiced. Most celiac sufferers also avoid oats, and that is likely wise considering the frequent contamination of oats with wheat from shared farms, harvesting equipment and storage facilities.

Table 4: Gluten-Derived IngredientsFood ingredients derived from wheat, rye, barley and related grains.

|

Celiac sufferers benefit from the commercial availability of gluten-free foods. The availability and diversity of gluten-free foods has expanded considerably in recent years. The popularity of gluten-free foods is driving this expansion. Clearly, gluten-free foods are being purchased (in the U.S. at least) by numerous consumers who do not have a diagnosis of celiac disease, although some of them may have non-celiac gluten sensitivity, a rather newly recognized form of gluten intolerance.

The Codex Alimentarius Commission has established guideline definition for gluten-free foods; these foods should contain no more that 20 ppm gluten. Many countries around the world have adopted the Codex guidance and use <20 ppm as the definition of gluten-free. However, some countries may not have yet adopted the 20 ppm guideline and may still use the former Codex guideline of <200 ppm gluten. On August 2, 2013, FDA issued a final rule defining "gluten-free" for food labeling of which went into effect August 5, 2014. The new federal definition standardized the meaning of "gluten-free" claims requiring a food to meet all the requirements of the definition, including that the food must contain <20 ppm of gluten.

The minimal eliciting dose for wheat, rye, barley, and related grains among celiac sufferers is unknown and is likely variable between affected individuals. Many individuals with celiac disease go to great lengths to avoid all sources of wheat, rye, barley, and triticale. While this has not been conclusively proven, a few isolated studies have concluded that levels of 10 mg of gliadin per day will be tolerated by most patients with celiac disease.

Detection

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) have been developed for the detection of residues of gliadin (wheat) in foods; most of these ELISAs also detect the related proteins from rye, barley, and other grains. These ELISAs are widely used in support of the development and marketing of gluten-free foods. The ELISA kits on the market allow the detection of gluten at levels of 10 ppm or above. Thus, the ELISAs can be used to assure that gluten-free products are properly labeled.

Background References

Rubio-Tapia A, Murray J. Gluten-sensitive enteropathy. In: Metcalfe DD, Sampson HA, Simon RA, eds. Food Allergy - Adverse Reactions to Foods and Food Additives. 4th ed. Malden MA: Blackwell Science. 2008:211-22.

Updated 3 March, 2017